The Known and Unknown Scriptures of 1 Clement

"Let us gaze earnestly at the blood of Christ and know how precious it is to his Father" (1 Clem. 7, 4).

Clement and the Septuagint (LXX)

Along with material in the Didache, 1 Clement is the oldest Christian text outside of the New Testament. The author gives no indication of being Jewish, but he is very familiar with the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament = LXX), which he cites frequently and at length, generally in its literal sense.1 This is important, because many Christians in the earliest Church (including at Rome) either rejected the Old Testament (Marcion) or approached it only through extensive allegory (Valentinus and Ps.-Barnabas). Others, such as Polycarp and Ignatius, show only limited knowledge of the Old Testament in general. Compared with the writings that would comprise the New Testament, the Old Testament was daunting in its scope, culturally unfamiliar, and could be difficult to interpret, as we see in the New Testament itself (Lc. 24, 25-27; Act. 8, 30-31). Centuries later in the time of Augustine, prophets like Isaiah remained mystifying even to well-educated Romans who had been raised in the Church (Aug., conf. 9, 5, 13).

Clement’s knowledge of the Old Testament is broad and thoroughgoing: He references the law, historical books, prophets, and wisdom literature, frequently citing extensive passages from the LXX. For example, he illustrates the humility of Christ by citing the entirety of Is. 53. This goes far beyond a mere literal reading; it is a thoroughgoing typological approach to the Old Testament:

τὸ σκῆπτρον τῆς μεγαλωσύνης τοῦ θεοῦ, ὁ κύριος Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, οὐκ ἦλθεν ἐν κόμπῳ ἀλαζονείας οὐδὲ ὑπερηφανίας, καίπερ δυνάμενος, ἀλλὰ ταπεινοφρονῶν, καθὼς τὸ πνεῦμα τὸ ἅγιον περὶ αὐτοῦ ἐλάλησεν· φησὶν γάρ· […] οὗτος τὰς ἁμαρτίας ἡμῶν φέρει καὶ περὶ ἡμῶν ὀδυνᾶται, καὶ ἡμεῖς ἐλογισάμεθα αὐτὸν εἶναι ἐν πόνῳ καὶ ἐν πληγῇ καὶ ἐν κακώσει. αὐτὸς δὲ ἐτραυματίσθη διὰ τὰς ἁμαρτίας ἡμῶν καὶ μεμαλάκισται διὰ τὰς ἀνομίας ἡμῶν· παιδεία εἰρήνης ἡμῶν ἐπ᾿ αὐτόν· τῷ μώλωπι αὐτοῦ ἡμεῖς ἰάθημεν. (1 Clem. 16, 2; 4-5).

The scepter of the majesty of God, the Lord Jesus Christ, did not come in the bragging of imposture nor arrogance, although he could have, but with a humble mind, just as the Holy Spirit spoke concerning him. For he says, […] “He bears our sins and suffers on our account, and we regarded him as being in suffering and pain and oppression. For he was wounded for our sins and has been weakened on account of our lawlessness. The chastisement of our peace is upon him. And by his stripe we were healed” (Is. 53, 4-5). (link)

Old Testament figures, according to Clement, proclaimed the coming of Christ, and thus provide a moral example for Christians:

Μιμηταὶ γενώμεθα κἀκείνων, οἵτινες ἐν δέρμασιν αἰγείοις καὶ μηλωταῖς περιεπάτησαν κηρύσσοντες τὴν ἔλευσιν τοῦ Χριστοῦ· λέγομεν δὲ Ἠλίαν καὶ Ἐλισαιέ, ἔτι δὲ καὶ Ἰεζεκιήλ, τοὺς προφήτας. (1 Clem. 17, 1).

We should become imitators of those who in the skins of goats and sheep went around proclaiming the coming of Christ—that is, Isaiah and Elijah, and also Ezekiel, the prophets. (link)

Elsewhere, Clement uses the Old Testament to help formulate his response to the Corinthians. He turns to exemplary figures who proclaimed repentance, like Noah, Jonah, and the prophets (1 Clem. 7-8) and cites examples of righteousness and faith in figures like Enoch, Abraham, Lot, and Rahab (1 Clem. 9-12). His call to repentance is preceded by a meditation on the blood of Christ, which extends the gift of repentance seen in the Old Testament to the whole world. The blood of Christ is the key to the Old Testament, and it holds Clement’s gaze, so to speak, through his entire letter:

ἀτενίσωμεν εἰς τὸ αἷμα τοῦ Χριστοῦ καὶ γνῶμεν, ὡς ἔστιν τίμιον τῷ πατρὶ αὐτοῦ, ὅτι διὰ τὴν ἡμετέραν σωτηρίαν ἐκχυθὲν παντὶ τῷ κόσμῳ μετανοίας χάριν ὑπήνεγκεν. (1 Clem. 7, 4).

Let us gaze earnestly at the blood of Christ and know how precious it is to his Father, because for our salvation it was poured out and offered to the whole world for repentance. (link)

The shedding of Christ was prophetically foretold in the Old Testament by the figure of Rahab’s scarlet sash. Far from being a “marginal reference to the scarlet cord,” as Simonetti argues,2 this is an important early example of typology (cf. Just., dial. 111):

καὶ προσέθεντο αὐτῇ δοῦναι σημεῖον, ὅπως ἐκκρεμάσῃ ἐκ τοῦ οἴκου αὐτῆς κόκκινον, πρόδηλον ποιοῦντες ὅτι διὰ τοῦ αἵματος τοῦ κυρίου λύτρωσις ἔσται πᾶσιν τοῖς πιστεύουσιν καὶ ἐλπίζουσιν ἐπὶ τὸν θεόν. ὁρᾶτε, ἀγαπητοί, ὅτι οὐ μόνον πίστις, ἀλλὰ καὶ προφητεία ἐν τῇ γυναικὶ γέγονεν. (1 Clem. 13, 7-8).

And they told her in addition to give a sign, that she should hang a piece of scarlet from her house, making it clear that through the blood of the Lord there will be redemption to all those believing and hoping in God. See, beloved, that not only faith but also prophecy is found in the woman. (link)

Clement also establishes Peter and Paul as moral examples beside the Old Testament figures. They are inheritors and continuators of the same tradition. Note that this is the earliest account of the martyrdom of both apostles:

Ἀλλ᾿ ἵνα τῶν ἀρχαίων ὑποδειγμάτων παυσώμεθα, ἔλθωμεν ἐπὶ τοὺς ἔγγιστα γενομένους ἀθλητάς· λάβωμεν τῆς γενεᾶς ἡμῶν τὰ γενναῖα ὑποδείγματα. […] Πέτρον, ὃς διὰ ζῆλον ἄδικον οὐχ ἕνα οὐδὲ δύο, ἀλλὰ πλείονας ὑπήνεγκεν πόνους καὶ οὕτω μαρτυρήσας ἐπορεύθη εἰς τὸν ὀφειλόμενον τόπον τῆς δόξης. διὰ ζῆλον καὶ ἔριν Παῦλος ὑπομονῆς βραβεῖον ἔδειξεν· ἑπτάκις δεσμὰ φορέσας, φυγαδευθείς, λιθασθείς, κῆρυξ γενόμενος ἔν τε τῇ ἀνατολῇ καὶ ἐν τῇ δύσει, τὸ γενναῖον τῆς πίστεως αὐτοῦ κλέος ἔλαβεν. δικαιοσύνην διδάξας ὅλον τὸν κόσμον, καὶ ἐπὶ τὸ τέρμα τῆς δύσεως ἐλθὼν καὶ μαρτυρήσας ἐπὶ τῶν ἡγουμένων, οὕτως ἀπηλλάγη τοῦ κόσμου καὶ εἰς τὸν ἅγιον τόπον ἀνελήμφθη, ὑπομονῆς γενόμενος μέγιστος ὑπογραμμός. (1 Clem. 5, 1; 4-7).

But to stop giving ancient examples, let us go to those contenders who have appeared more recently. Let us take the excellent examples of our generation […] Peter, who on account of unjust jealousy bore not one, not two, but many sufferings, and thus having witnessed he went to the deserved place of glory. Because of jealousy and strife, Paul demonstrated the prize of endurance. Seven times he bore chains, was banished, stoned, became a herald in the east and the west, and received the renowned fame of his faith. He showed righteousness to the whole world, having come to the limit of the west and having born witness to the rulers. Thus, he was set free from the world and was brought to the holy place, having become a great example of endurance. (link)

Clement and the New Testament

As far as the New Testament goes, it is evident that there is nothing like a canon.3 The gospels appear to be unknown to the author, and when he quotes Jesus’ words they do not match any known text (except for 2 Clem.). He does explicitly mention 1 Cor. and seems to know other works from the New Testament (such as Heb.). The words of Christ and Paul are cited along with the Old Testament, and are thus clearly also thought to carry the authoritative weight of scripture. As Ehrman argues,

“[W]e can see here the very beginnings of the process in which Christian authorities (Jesus and his apostles) are assigned authority comparable to that of the Jewish Scriptures, the beginnings, in other words, of the formation of the Christian canon.”4

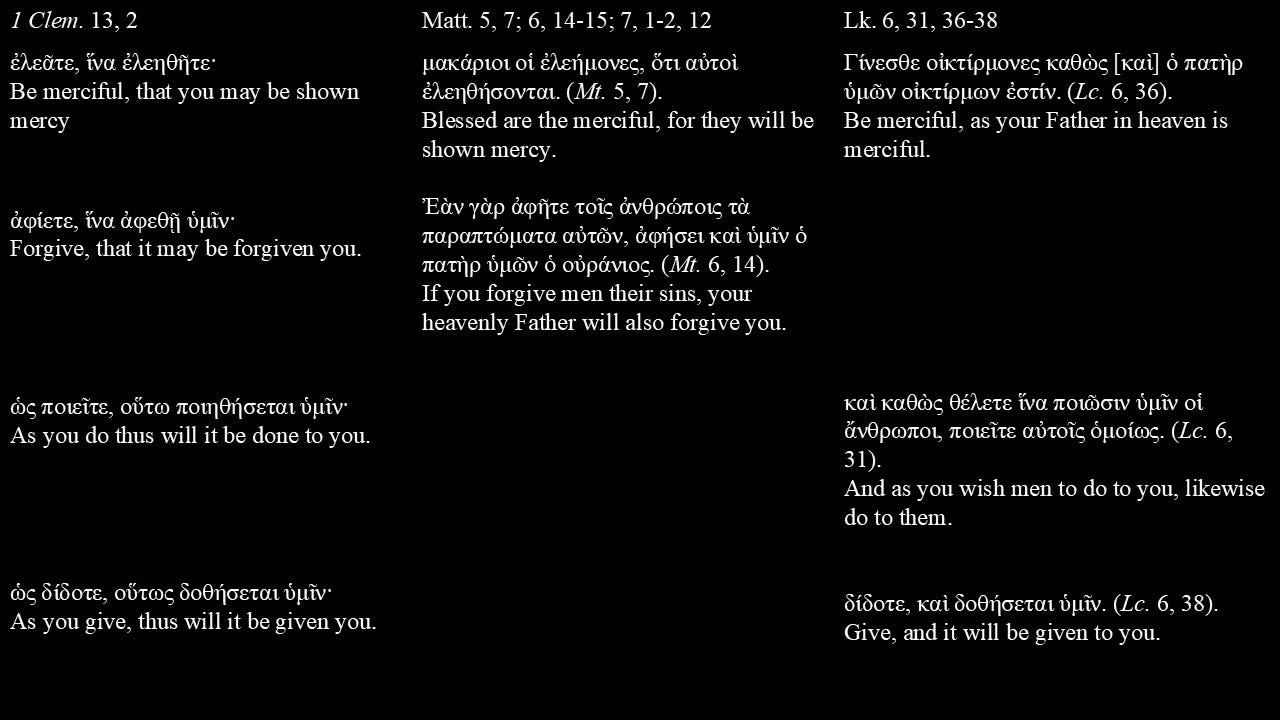

The words of Jesus are also cited, but never precisely in the tradition of the Gospels, thus showing probable dependence on other oral traditions. The same dependency on oral traditions can be seen in the Didache:

οὕτως γὰρ εἶπεν· ἐλεᾶτε, ἵνα ἐλεηθῆτε· ἀφίετε, ἵνα ἀφεθῇ ὑμῖν· ὡς ποιεῖτε, οὕτω ποιηθήσεται ὑμῖν· ὡς δίδοτε, οὕτως δοθήσεται ὑμῖν· ὡς κρίνετε, οὕτως κριθήσεσθε· ὡς χρηστεύεσθε, οὕτως χρηστευθήσεται ὑμῖν· ᾧ μέτρῳ μετρεῖτε, ἐν αὐτῷ μετρηθήσεται ὑμῖν. (1 Clem. 13, 2).

For thus [Christ] said, “Show mercy, so that you may be shown mercy. Forgive, so that it may be forgiven you. For as you do, thus it will be done to you. As you give, thus will it be given to you. As you judge, thus will you be judged. As you show kindness, thus will kindness to be shown to you. With the measure that you measure, in this it will be measured for you.” (link)

In the following charts, notice that in the preceding passage Clement does not actually cite the gospels, even though his material is similar and can appear identical in translation:

The Unknown Scriptures

Other scripture is quoted from unknown sources. Tantalizingly, the same quote that appears to refer to the lack of an arriving eschaton also appears in 2 Clem., even though both works are (almost certainly) by separate authors and the words are slightly different.

πόρρω γενέσθω ἀφ᾿ ἡμῶν ἡ γραφὴ αὕτη, ὅπου λέγει· ταλαίπωροί εἰσιν οἱ δίψυχοι, οἱ διστάζοντες τῇ ψυχῇ, οἱ λέγοντες· ταῦτα ἠκούσαμεν καὶ ἐπὶ τῶν πατέρων ἡμῶν, καὶ ἰδού, γεγηράκαμεν, καὶ οὐδὲν ἡμῖν τούτων συνβέβηκεν. ὦ ἀνόητοι, συμβάλετε ἑαυτοὺς ξύλῳ· λάβετε ἄμπελον· πρῶτον μὲν φυλλοροεῖ, εἶτα βλαστὸς γίνεται, εἶτα φύλλον, εἶτα ἄνθος, καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα ὄμφαξ, εἶτα σταφυλὴ παρεστηκυῖα. ὁρᾶτε, ὅτι ἐν καιρῷ ὀλίγῳ εἰς πέπειρον καταντᾷ ὁ καρπὸς τοῦ ξύλου. (1 Clem. 23, 3-4; cf. 2 Clem. 11, 2-3).

May that scripture be far removed from us which says, “How miserable are those of two minds, who doubt in their soul, who say, ‘We have heard these things from our fathers, and see, we have grown old, and none of them has happened to us.’ You fools! Compare yourselves to a tree. Take a vine: First it sheds its leaves, then a bud appears, then a leaf, then a flower, and after these an unripe grape, and then a bunch of grapes fully grown. See that in a little time the fruit of the tree arrives at ripeness.” (link)

There is another citation in 1 Clem. 46, 2 from an unknown scriptural source.

Τοιούτοις οὖν ὑποδείγμασιν κολληθῆναι καὶ ἡμᾶς δεῖ, ἀδελφοί. γέγραπται γάρ· κολλᾶσθε τοῖς ἁγίοις, ὅτι οἱ κολλώμενοι αὐτοῖς ἁγιασθήσονται. (1 Clem. 46, 2).

Therefore, it is necessary that we also be joined to these examples. For it has been written: “Join yourselves to the holy, for those joined to them will be made holy.” (link)

Clement references and shows clear knowledge of 1 Cor., esp. 37, 5 and 47, 1-3. Thus, even within a few decades of writing, the letters of Paul are widely known and cited even by those outside the communities. In this case, they are being cited by Rome back to Corinth, and knowledge of them is assumed.

λάβωμεν τὸ σῶμα ἡμῶν· ἡ κεφαλὴ δίχα τῶν ποδῶν οὐδέν ἐστιν, οὕτως οὐδὲ οἱ πόδες δίχα τῆς κεφαλῆς· τὰ δὲ ἐλάχιστα μέλη τοῦ σώματος ἡμῶν ἀναγκαῖα καὶ εὔχρηστά εἰσιν ὅλῳ τῷ σώματι· ἀλλὰ πάντα συνπνεῖ καὶ ὑποταγῇ μιᾷ χρῆται εἰς τὸ σώζεσθαι ὅλον τὸ σῶμα. (1 Clem. 37, 5; cf. 1 Cor. 12, 12-27).

Take our body: The head apart from the feet is nothing, and thus neither are the feet apart from the head. But the least parts of our body are necessary and useful for the whole body. But all parts breathe together and are subordinated to a single order for the salvation of the whole body. (link)

Ἀναλάβετε τὴν ἐπιστολὴν τοῦ μακαρίου Παύλου τοῦ ἀποστόλου. 2. τί πρῶτον ὑμῖν ἐν ἀρχῇ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου ἔγραψεν; 3. ἐπ᾿ ἀληθείας πνευματικῶς ἐπέστειλεν ὑμῖν περὶ ἑαυτοῦ τε καὶ Κηφᾶ τε καὶ Ἀπολλώ, διὰ τὸ καὶ τότε προσκλίσεις ὑμᾶς πεποιῆσθαι. (1 Clem. 47, 1-3).

Take up the epistle of the blessed Paul the apostle. What did he write to you first in the beginning of the gospel? In truth he sent you a letter in the spirit concerning himself and Cephas and Apollos, on account of the factions that you were even then making for yourselves. (link)

ἐδηλώθη γάρ μοι περὶ ὑμῶν, ἀδελφοί μου, ὑπὸ τῶν Χλόης ὅτι ἔριδες ἐν ὑμῖν εἰσιν. λέγω δὲ τοῦτο, ὅτι ἕκαστος ὑμῶν λέγει, Ἐγὼ μέν εἰμι Παύλου, Ἐγὼ δὲ Ἀπολλῶ, Ἐγὼ δὲ Κηφᾶ, Ἐγὼ δὲ Χριστοῦ. (1 Cor. 1, 11-12).

“For this was made known to me concerning you, my brothers, by those with Chloe, that there are factions among you. I mean this: that each of you says, ‘I belong to Paul’; ‘I belong to Apollos’; ‘I belong to Cephas’; ‘I belong to Christ.’” (link)

In conclusion, 1 Clem. demonstrates extensive knowledge of the Old Testament, but interprets it always in light of Christ. Not only did the prophets proclaim the coming of Christ, but prophetic moments are found elsewhere in the Old Testament, like the scarlet cord of Rahab (Ios. 2, 18).5 Clement also uses Old Testament figures as moral examples, demonstrating their continued relevance along with the martyrs as models of Christian behavior. There is as yet no canonical New Testament, and Clement cites the teachings of Jesus probably from oral tradition. He is aware of Pauline letters, which he cites effectively to the Corinthians. He cites otherwise unknown works as scripture. The openness of the New Testament canon and the reliance on oral tradition is certainly not unique to Clement: The Didache probably shows a similar reliance on oral tradition. Finally, 1 Clem. itself appears to have been treated as scripture in Corinth for decades after its composition (Eus., h. e. 4, 23, 9-11), and even appears in the 5th century Codex Alexandrinus.

M. Simonetti, Biblical Interpretation in the Early Church, trans. J. Hughes, New York 1994, 12.

Ibid., 13.

B. Ehrman, The Apostolic Fathers, Volume 1. Harvard 2003 (LCL 24), 26.

Ibid., 26.

I cannot agree with M. Simonetti, Biblical Interpretation, 13, that “the fact that he presents only one passing instance of [typology] might show a reserved attitude towards this type of interpretation.”